Steven G

Elite Member

- Joined

- Dec 30, 2014

- Messages

- 14,598

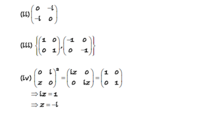

You really should argue that there are no larger groups whose order is more than 5 and less than 10. I do realize that this will be trivial but I fell necessary. What do you think?I can show that this is a trick question Lets call \(\displaystyle P\) the superstition that \(\displaystyle a(bc)=a\).

So we accept both \(\displaystyle a^2=b~\&~a^3=c\) as true in the following two Cayley tables:

Table I \(\displaystyle \begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

\circ &|&e&a&b&c&d \\

\hline

e&|&e&a&b&c&d \\

a&|&a&b&c&d&e \\

b&|&b&c&d&e&a \\

c&|&c&d&e&a&b \\

d&|&d&e&a&b&c \end{array}\) TABLE II \(\displaystyle \begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

\circ &|&e&a&b&c \\ \hline

e&|&e&a&b&c \\

a&|&a&b&c&e \\

b&|&b&c&e&a \\

c&|&c&e&a&b \end{array}\)

Both of the tables conform to the accepted two conditions, but only table I conforms to the other condition \(\displaystyle P:~a(bc)=a\).

Note that both tables represent a group generated by \(\displaystyle a\)

In order to accomplish that we had to introduce an element \(\displaystyle d\). Now the group is order five and each non-rival element is order five.