prepforcalc

New member

- Joined

- Jan 6, 2018

- Messages

- 22

Getting the "1/2" in int[0,t][v_0 + at] dt = v_0 + (1/2)at^2 the calculus way!

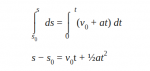

I attached a screenshot. Would someone remind me of the calculus step or rule that allows one to go from the upper line to the lower line and get 1/2? The 1/2 part is all that I'm confused about.

. . . . .\(\displaystyle \large{ \displaystyle \int_{s_0}^s\, ds\,\, \int_0^t\, (v_0\, +\, at)\, dt }\)

. . . . .\(\displaystyle \large{ s\, -\, s_0\, =\, v_0t\, +\, \frac{1}{2}at^2 }\)

PS - I already know how to do this the non-calculus way. Per my username, I'm sharpening my calculus skills. Thanks.

I attached a screenshot. Would someone remind me of the calculus step or rule that allows one to go from the upper line to the lower line and get 1/2? The 1/2 part is all that I'm confused about.

. . . . .\(\displaystyle \large{ \displaystyle \int_{s_0}^s\, ds\,\, \int_0^t\, (v_0\, +\, at)\, dt }\)

. . . . .\(\displaystyle \large{ s\, -\, s_0\, =\, v_0t\, +\, \frac{1}{2}at^2 }\)

PS - I already know how to do this the non-calculus way. Per my username, I'm sharpening my calculus skills. Thanks.

Attachments

Last edited by a moderator: